Generating trust: Safeguarding authenticity in typography.

Bryan Comeau - Senior Director, Software Engineering

In our modern world, fonts are all around us. In our books, on our phones, and across our roadways, fonts help us navigate the spaces we engage with. Fonts are powerful. They play a pivotal role in visual communication, conveying messages, establishing brand identities, helping make content more accessible, and shaping user experiences across mediums.

With this power, however, there are new opportunities, responsibilities, and challenges. It’s easier than ever for anyone to create designs and images, thanks both to consumer-level design tools and generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). Over the past year in particular, the world has watched as GenAI has fabricated increasingly sophisticated content by manipulating information, text, fonts, graphics, logos, photographs, videos, and audio tracks in mere seconds.

But what does this mean for type designers and consumers?

Creating with fonts in the age of AI.

As generative AI’s ability to create new, sharp-looking designs has increased, the lines between human-designed fonts and those conceived by algorithms have begun to blur. The artificial production of content raises complex questions about what it means to create. What makes something original? When can you claim authorship? Should AI engineers receive credit for the AI-generated content prompted by an AI user? How important is knowing whether a product is AI-generated or human-designed to users?

Threaded throughout this conversation is the real and understandable anxiety of many that generative AI creates more opportunities for their own work to be taken and presented as someone else’s creation or intellectual property. As GenAI technology advances to the point where it can emulate human design capabilities, font designers now must contend with the potential for their design work to be erroneously attributed to AI-generated counterparts.

Why typographic authorship matters for users.

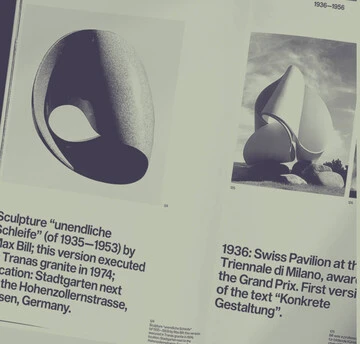

Fonts aren’t just created, they are also used and relied upon. It’s imperative that users feel they can trust the digital elements they interact with across websites and applications. While a lot of the discussion around GenAI has focused on helping consumers of online content spot altered photos, videos, and sound clips, less has been said regarding text and fonts.

But the fight against misinformation and content manipulation is just as important in text as it is in pictures and sound. The subtle nuances of different typefaces can influence perceptions and emotions. Misinformation and content manipulation involving fonts can lead to deceptive branding, forged documents, or altered text that misguides audiences.

Safeguarding the authenticity of fonts becomes crucial not only for preserving the credibility of visual communication but also for upholding the integrity of information in a world where digital content is easily manipulated.

So how can users and designers alike get the information they need to begin to figure out what content is genuine and more likely to be trustworthy, and what content needs to be further interrogated?

Building trust through transparency.

Unfortunately, many of the files we encounter online don’t provide us with verified information on who created the file or how the file data may have been manipulated before it reached us. However, there are now initiatives that are working proactively to try to change that.

One such initiative is the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity, or C2PA, which hopes to mitigate the pervasiveness of misleading information online through the development of technical standards that certify the source and edit history of media content.

How does it work? Content Credentials, based on the C2PA open technical standard, provide a way for creators of any type of digital content, including images, videos, audio, and fonts, to assert in a verifiable way any information they wish to disclose about the creation of that content and any actions taken to the file since its creation.

By disclosing the provenance of a file, Content Credentials help content consumers to make more informed decisions on the trustworthiness of that content. Who made the content? Has it been edited since then? If so, how and by whom? Have the edits altered the original message? Empowering consumers of digital content with the ability to verify the authenticity of that content forms the foundation of safeguarding content authenticity.

Two examples: Fonts and videos.

With Content Credentials, when a font designer creates a brand-new font, they can attach information to the file about the date it was created and the tools that were used. They may even be able to include information that could be used in downstream processes, such as “do not train” assertions for machine learning.

Font consumers can then validate this information to ensure that the font file and manifest information weren’t altered. They can also review any changes that were later made to the original font file. All of this helps to build confidence that the font file was not maliciously altered and that it is genuine.

Another great asset that Content Credentials bring is the ability to add origin and change history information to all of the individual data types present in one media file. When working with a multimedia file, such as a video, that contains a moving image, audio, and perhaps subtitles, there are even more opportunities for potential manipulation. In the age of deepfakes, how can the everyday user decipher whether or not a video is fully authentic?

Content Credentials provide a way to attach provenance information to each element of the video. The information is chained together, and consumers are then able to validate each of the components individually to ensure none of the content has been altered.

An important caveat.

It is vital to note that Content Credentials are value-neutral, meaning that they do not provide a judgement on whether a given set of provenance data is “good” or “bad.” Instead, Content Credentials verify that the assertions included with the underlying digital data asset are correctly formed and free from tampering.

What’s next?

Specific case studies directly applying Content Credentials to fonts are not yet widely available. However, Monotype has already started taking a detailed look into how initiatives like Content Credentials could be beneficial in the future for securing fonts and preventing misinformation. Progress has also been made to add support for font assets to the Content Credentials and early proof of concepts show promise.

Within the upcoming year, Monotype will explore applying Content Credentials to select fonts and observing the results, all while recognizing that implementing Content Credentials in fonts may face challenges related to standardization, balancing security with accessibility, and the general effectiveness of Content Credentials in preventing font-related misinformation.

By addressing the challenges presented by creating and trusting digital media in the era of GenAI, initiatives using the integration of technologies such as Content Credentials aim to fortify the reliability of digital assets, contributing to a more trustworthy and transparent online environment.

Bryan Comeau is Senior Director for Software Engineering at Monotype. He loves thinking about technology and type, brainstorming collaboratively on ways to improve text rendering and language support across an array of consumer electronic devices, medical equipment, and automotive platforms.

For more innovation and thought leadership across the industry, visit Monotype Labs.

![[Webinar]: The science behind the emotional impact of type. [Webinar]: The science behind the emotional impact of type.](/sites/default/files/styles/380x190/public/2022-05/Monotype%20x%20Neurons.-low.gif?itok=I-ST9WUK)